The Christmas Cough

Published in the Ashland Daily Press

February 2, 2019

Mom was seven years old when she came home from school with a non-stop cough. Mom was one of those kids who had seasonal allergies, so her coughing and runny nose had become more of a nuisance for her, than a warning. So instead of heading indoors, she followed her two brothers toward their backyard sledding hill. It was the first real snowfall of the season.

“Sonny, go and get Dad,” Grandma yelled to Mom’s brother from the door of their Country Store. “It’s time for supper!” Grandpa was usually in the barn that time of day feeding the animals.

Mom ran into the housing quarters of the store and glanced toward the sewing machine. Bob Fisk, Mom’s teacher, had asked Grandma to make Mom a pink dress for the Namakagon School’s Christmas program.

“Can I try it on?” Mom asked, coughing through her question.

“Cover your mouth,” Grandma directed. “You can try it on after supper.”

At the dinner table, Mom coughed and chattered on about the part she landed as a lost doll in the play. She still remembers practicing her lines after supper while helping with the kitchen cleanup.

“Are you feeling okay Marion?” Grandma Anderson asked while pouring a kettle of boiling water into the kitchen’s wash basin.

“Can I still be in the play if I’m sick?” Mom asked.

“Come here,” Grandma said, while hand-pumping enough well water to make the dishwater manageable. She dried her hands on her apron before resting the back of her hand on Mom’s forehead. “You feel a bit warm. Why don’t you go upstairs and lay down. I’ll come up and check on you when I’m done here.”

Later, in the dim light of the kerosene lamp, Grandma combed the damp hair from Mom’s face and uttered, “You’re burning up.”

Mom started mumbling two words from her memorized lines, “ . . . I’m lost . . . I’m lost . . .”

I’m guessing the blood drained from my grandmother’s face before she shrieked to Grandpa, “we need to get Marion to the hospital!”

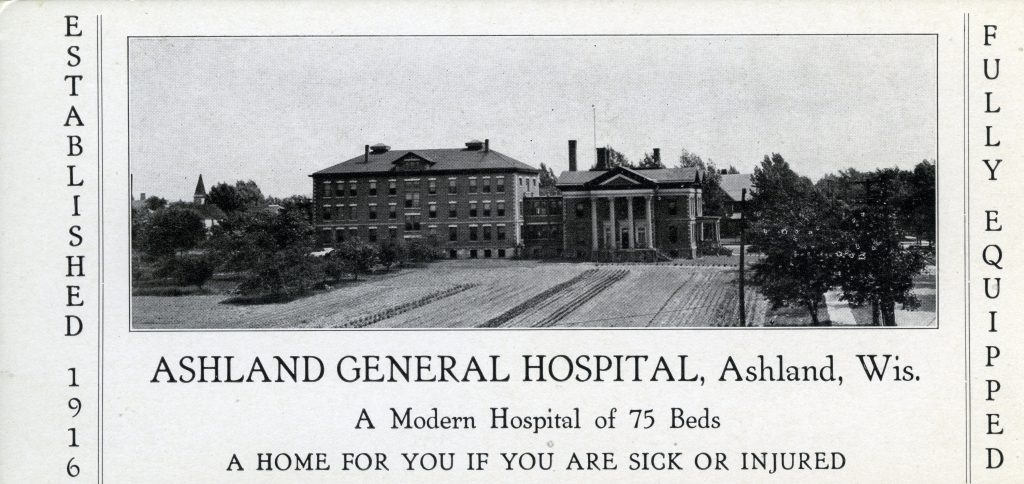

It was an hour’s drive to the Ashland General Hospital. With no heater in the car, Mom remembers how the chill of the winter night seeped through the panels of the car and stung like icicles against her feverish skin.

Dr. Smiles Sr. immediately diagnosed Mom with bronchial pneumonia. By morning, the disease progressed into double pneumonia, a potentially lethal infection in both lungs. It was before the advent of antibiotics, so one third of the people that were hospitalized with this diagnosis would not survive.

Mom’s temperature spiked as high as 108 degrees, the average stuck around 105. In a few days, the illness progressed into lobar pneumonia, a severe infection in the major lobes of the lungs.

The prognosis was grim.

Mom says the hospital staff started to ignore the strict hospital guidelines, it was hard for them to discipline a child so near death. They instead turned their head and allowed her to move freely from her hospital room, through the lobby, and into the parlor where she’d go looking for her mother.

Mom still shivers when she retells how she felt when her fevered bare feet touched the linoleum floor.

“Brrrrr,” Mom says laughing. “I thought that the hospital was saving on heat. And here it was me!”

Grandma must have felt helpless watching the nurses care for her daughter. She noticed they would open the window when Mom’s temperature went up, so she started doing the same. Mom remembers when one of her less favorite nurses yelled at Grandma for doing that.

It was just short of a week before Christmas when Dr. Smiles explained to my grandparents, “it is possible that this may be your daughter’s last Christmas.”

Mom hated the constant poke of needles into her lungs that was necessary to get the mucus out. She was too young to understand that without that procedure, she would die. Grandma promised Mom a doll for Christmas. It was a bargaining chip so Mom would listen to the doctors and do what they said.

They gave Mom the gift two days before Christmas.

Mom fell asleep that night, cradling her new doll. When she woke the following morning, she rolled over and knocked the doll off the bed. When the porcelain head hit the unforgiving floor, a ‘crack’ echoed in the silent room. Mom started to cry when she saw that her brand-new doll had sustained a gash that could not be mended.

It was Christmas Eve when a nurse came into Mom’s room with a tray covered with a sterile cloth. The nurse smiled at her then looked toward the tray. “The doctor is giving you a Christmas present later . . .”

When the doctor came into the room and uncovered the cloth, Mom said she was shaken to see not a toy, but a needle seven inches long. And while she was processing the horrible change of events, the doctor picked up the needle and jabbed it in her chest, right between her ribs. When she started screaming, numerous assistants flocked beside her bed and held her down.

The doctor tried to suction out the mucus but the procedure failed. It was determined that an emergency surgery would have to be performed.

Dr. Weeks, the surgeon, didn’t want to use a sedating anesthesia because he felt Mom was too weak and her body wouldn’t take it. He gave her a local anesthetic to numb the incision area in her chest.

Mom said she shrieked when she saw the surgeon was sawing at her rib. When she became delirious, Dr. Weeks determined it would be better to risk the sedation. He stopped the procedure and ordered the staff to give Mom ether. Once she was sedated, Dr. Weeks cut the rib and entered the lung and sucked out the mucus.

When Mom woke, exhausted and looking defeated, Grandma made her a promise. She said she’d leave the candles on the tree and light them one more time when they got home.

The lungs began to heal.

Dr. Smiles called it a miracle.

Once the fever broke, mom remembers peeling sheets of dead skin off her body, littering the sheets of her hospital bed. And then one day she went deaf.

At first, Dr. Smiles thought her hearing loss was due to the high fever. But after a few short days, Mom’s hearing started to return. Dr. Smiles told Grandma, “the dead skin in the inner ear must have plugged up the canal.”

Mom was discharged seven weeks after she was admitted to the hospital, on February 1, 1936. She was expected to make a full recovery.

Once home, Grandpa and Grandma lit the wax candles that were clipped onto the tree like they promised. Even though the tree was stored in a cold room the past weeks, it was still dried out enough to be a fire hazard. My grandparents blew out the candles almost immediately after they were all lit.

It was the last time Mom’s family used wax candles in their Christmas tree. Electricity would come that summer.

For my mom’s family, the Christmas of 1935 was about a miracle. The year of 1936, that began with a kind of thankfulness, ended with the promise of significant changes to come.